Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) is a recurrent depressive disorder defined by the increase of depressive symptoms during specific seasons, most commonly fall and winter, followed by a relief of symptoms occurring in spring or summer (Rosenthal et al., 1984). SAD has a significant impact on mental health and well-being, affecting various aspects of daily functioning and quality of life. Understanding the underlying mechanisms contributing to SAD and identifying effective treatment strategies are crucial for addressing this condition comprehensively.

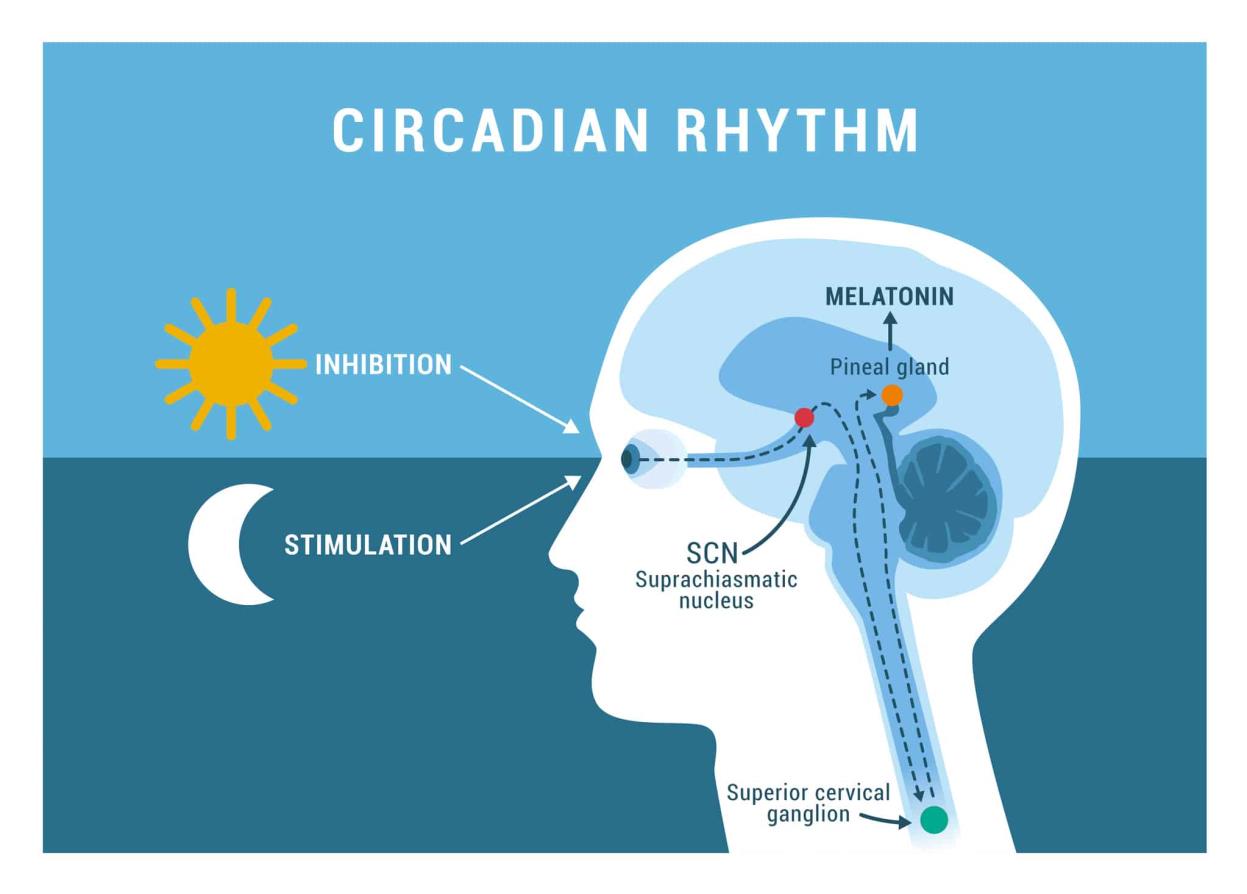

The etiology of SAD is complex and consists of biological, psychological, and environmental factors. Reduced exposure to sunlight during fall and winter months is considered a primary trigger for SAD, leading to disruptions in circadian rhythms, alterations in neurotransmitter levels (particularly serotonin and melatonin), and changes in hormonal regulation (Rohan et al., 2009). Genetic predispositions, family history of mood disorders, and psychosocial stressors may also contribute to individual susceptibility to SAD.

Individuals with SAD often experience a range of depressive symptoms, including low mood, drowsiness, fatigue, hypersomnia, increased appetite with carbohydrate cravings, weight gain, social withdrawal, and diminished interest in previously enjoyed activities (Levitt et al., 2000). Diagnosis of SAD is based on clinical assessment, including a thorough evaluation of symptoms, (initially and during) how often it reoccurs during the season and impairment in social, career related, or other important areas of functioning. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) includes diagnostic criteria that can be used to detect and categorize SAD.

SAD tends to affect approximately 1-10% of the population, with higher rates found in regions with shorter daylight hours and greater seasonal shifts in sunlight exposure (Magnusson, 2000). SAD has a broader cultural and economic impact than just individual suffering, including decreased productivity, absence from work or school, and a higher use of healthcare. Several treatment options have been developed for managing SAD, including pharmacotherapy, light therapy (also known as bright light therapy or phototherapy), psychotherapy, and lifestyle changes. Light therapy, involving exposure to bright artificial light in the morning, has become a primary treatment option for SAD, with meta-analyses confirming its efficacy in reducing depressive symptoms (Golden et al., 2005). Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has also demonstrated effectiveness in addressing maladaptive thought patterns and behaviors associated with SAD, providing useful coping skills, and encouraging adaptive responses to seasonal changes (Rohan et al., 2007).

Research endeavors are still in progress to investigate new treatment options and explain the fundamental causes of SAD. The developments in chronobiology, neuroscience, and genetics have provided valuable insights into the pathophysiology of SAD, which has made it possible to use personalized treatment strategies. Furthermore, research on the effectiveness of new interventions, such as dawn simulation, negative air ionization, and lifestyle modifications, offers hopeful paths for enhancing treatment outcomes and improving long-term prognosis for individuals with SAD. Seasonal Affective Disorder is a major public health concern, affecting many individuals during the fall and winter months. We can better understand this complex disorder and maximize clinical treatments to improve outcomes for affected patients by thoroughly analyzing the etiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, prevalence, treatment choices, and recent research results related to SAD. To improve attempts to lessen SAD's negative effects on mental health and wellbeing and to increase our understanding of the disorder, researchers, doctors, and legislators must continue their collaborative efforts.

References

Golden, R. N., Gaynes, B. N., Ekstrom, R. D., et al. (2005). The efficacy of light therapy in the treatment of mood disorders: a review and meta-analysis of the evidence. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(4), 656-662.

Levitt, A. J., Joffe, R. T., & Moul, D. E. (2000). Evidence for a biological mechanism in seasonal affective disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 59(2), 149-160.

Magnusson, A. (2000). An overview of epidemiological studies on seasonal affective disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 101(3), 176-184.

Rohan, K. J., Mahon, J. N., Evans, M., Ho, S. Y., Meyerhoff, J., Postolache, T. T., & Vacek, P. M. (2009). Cognitive-behavioral therapy vs. light therapy for preventing winter depression recurrence: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 10(1), 90.

Rohan, K. J., Roecklein, K. A., & Lacy, T. J. (2007). Cognitive-behavioral therapy, light therapy, and their combination in treating seasonal affective disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 100(1-3), 25-34.

Rosenthal, N. E., Sack, D. A., Gillin, J. C., Lewy, A. J., Goodwin, F. K., Davenport, Y., ... & Wehr, T. A. (1984). Seasonal affective disorder: a description of the syndrome and preliminary findings with light therapy. Archives of General Psychiatry, 41(1), 72-80.

Marisha Sai Jasmine Sahatoo

University of Waterloo

*This information is not intended to replace psychotherapeutic and/or medical advice or practices. They are for educational purposes only.